Yesterday, our friends over at Hammer & Rails (whom if you’re a Purdue fan and you’re not reading, you are missing out), put together an introspective look at whether Morgan Burke is under-appreciated by Purdue fans. The article makes quite a few compelling arguments for why Burke is doing a good job, but we just can’t bring ourselves around because of a few problems.

The biggest, in our opinion, is that Morgan Burke is directly responsible for the revenue situation faced by Purdue at the moment. The H&R article takes an approach of comparing the state of Purdue athletics in 1993 compared to Purdue athletics in 2015, and somewhat directly gives Burke credit for things that were either A) largely common sense or necessary (new and upgraded facilities) B) Largely beyond his (direct) control (NCAA Championships, bowl games, Big Ten Championships, or C) more directly attributable to a windfall of television revenue than anything else (and frankly, that windfall is nothing more than the stroke of luck in Purdue being a charter member of the Big Ten, and said conference turning into a money machine 100 years after its foundation). As an aside, could you imagine Purdue’s revenue situation if we were instead in the Big XII? Replace Iowa State with Purdue and I think the Boilermakers are going down a similar path (no value in a regional sports network, limited appeal within their home state, and no real opportunity to grow).

We agree, as a whole, Purdue is a lot better off than it was in 1993. The problem is this: so is everybody else. TV revenues across the NCAA have gone up dramatically. Football bowl revenues are up significantly (which is typically split by conference). The NCAA Men’s Basketball tournament TV contract crossed over $100 million a year in the 2000s. The NCAA, as a non-profit, ends up passing that on to member institutions. This isn’t even including the elephant in the room: conference television network revenues.

Furthermore, the assertion that the Purdue Board of Trustees was tight with the purse strings is, while relatively true, not absolutely true. It was only in 2005 that the athletics department completely weaned itself off of subsidies from the academic side of the business (though nominally, subsidies continued until 2007). Coincidentally, this draindown of school revenue was right around when the BTN went from idea stage to launch.

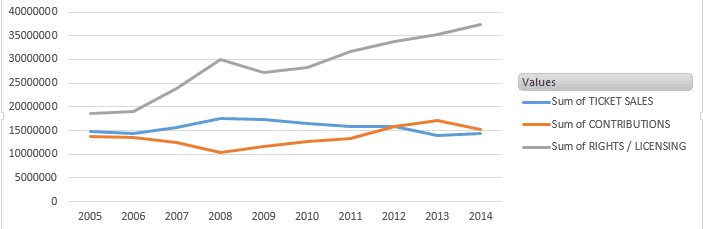

More or less, we’re saying that Purdue has been a “free-rider” on the coat tails of the Big Ten, and that’s hardly attributable to Burke’s keen business sense. In fact, we only have to look at That School Down South to see what the revenue implications of the last ten years have been. First, we’ll take a look at Purdue’s revenues from its three main sources (ticket revenue, individual donations, and rights/licensing agreements):

You can clearly see the skyrocket of rights and licensing revenue, most of which presumably from BTN. Perhaps most alarming is the rather flat ticket sales, with ticket sale revenue in 2005 totaling to $14.8 million ($18.1 million in 2014 dollars.) In 2014, ticket revenue was $14.4 million. Adjusted for inflation, that’s a decrease of 22%. Contributions, on the other hand, climb from $13,7 million to $15.3 million. While nominally a decrease in 2014 adjusted dollars, there’s a lot of noise in the data (As you can see from the spike in 2013, presumably from the Hazell hiring). So in order to really see how the Boilermakers are doing, let’s take a look at IU:

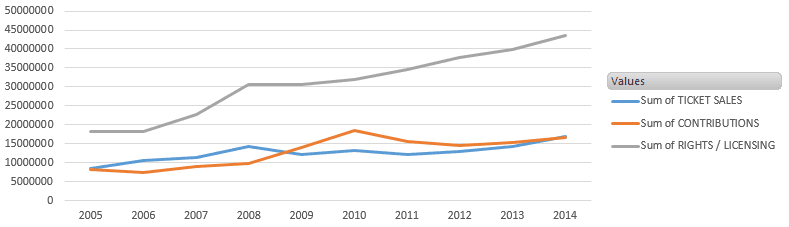

That chart looks a lot more like what one would expect. A slow increase in both contributions (again with some noise probably single handedly attributable to the Cody Zeller signing), and ticket revenue. Similar to Purdue, rights and licensing revenues skyrocket.

What’s most alarming in this comparison is to see what happened from 2005 to 2015. In 2005, Purdue had $51.3 million in revenue. IU? $38 million. In 2014, Purdue ended up with $71.3 million, while IU leapfrogged the Boilermakers with $84.6 million. And frankly, as Boilermakers, if we’re not going to use IU as the benchmark for failure, what are we even doing here?

Overall, the Burke legacy will likely be very similar to that of Joe Tiller. Tiller took Purdue football (and perhaps NCAA football as a whole) into the 21st century with the spread offense. Morgan Burke has done a good job at bringing Purdue to a status of “performing” but much like Tiller, some fresh talent is needed to get Purdue “over the hump.” H&R places the blame on the BoT, but I tend to think that those on the BoT would recognize the power that a successful athletic institution has in benefiting an academic institution. In short, a good football or basketball team is worth more than any amount of advertising.

This isn’t more clear than 70 miles down the road in Indianapolis. After an NCAA Basketball Final appearance, Butler estimated that it received $639 million in unpaid TV, print, and online media publicity. What happened next? Higher applicant pool, allowing more selective criteria , and thus benefiting the academic reputation of the school (alternatively, more volume, which would mean more tuition money.) Athletics largely functions as a giant money making marketing department for a university, and is one way that some universities can find ways to attract top academic talent, which benefits the institution as a whole. You can’t tell me that Duke isn’t pulling in kids when they see Cameron rocking. Meanwhile, the crickets chirp in Ross-Ade waiting for the next Drew Brees, who might’ve already fallen through the fingers, given that Purdue has been all but absent on the national stage for nearly a decade in football.

But as the Tiller story taught us all, it’s not enough to replace the guy who got you there. You need to make sure that you have the right talent ready to take you to the next level. The only question that remains is whether that talent is willing and able to take a look at West Lafayette.